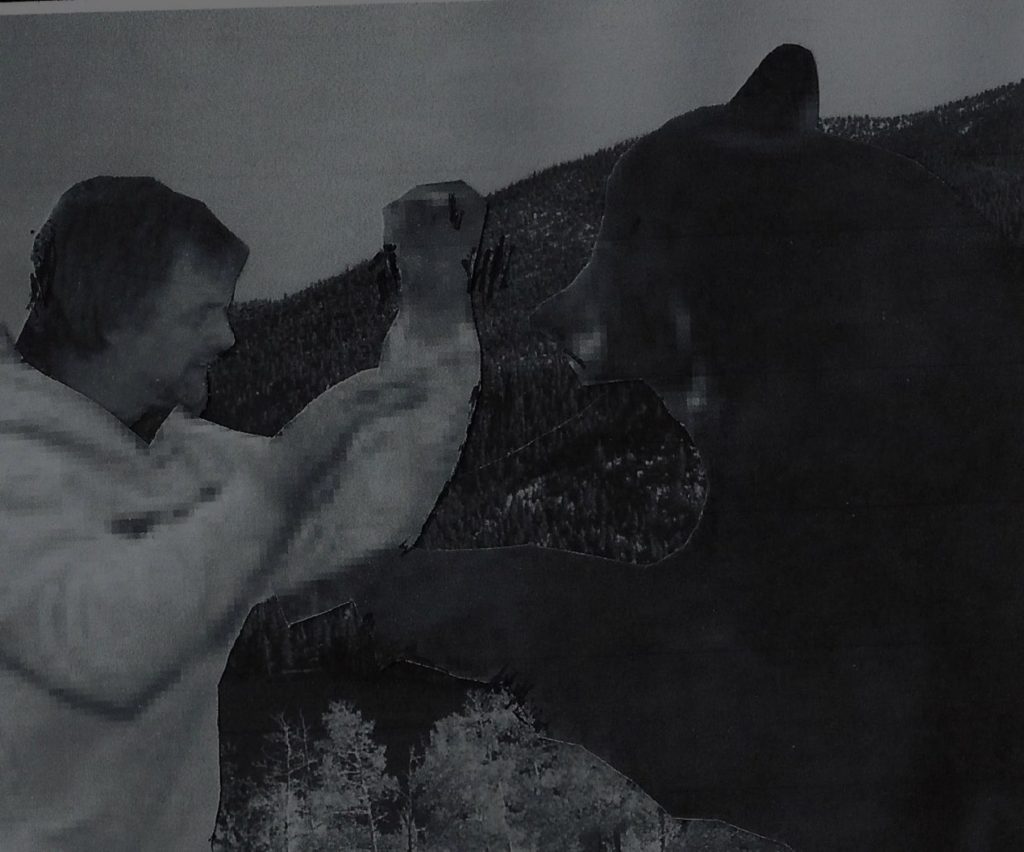

His daughter thinks he’s making it up, and he has yet to produce a single credible witness, but Tom loves to wrestle bears. He wrestles them while on family vacations in national parks. He wrestles them while camping in the mountains near his Colorado home. The bears typically win, but Tom derives a great deal of satisfaction from the contest itself.

His other interests are somewhat more predictable and more easily verified. These include reading, listening to music, creating his own music on a four-track analog recorder using a variety of instruments, two of which he actually knows how to play, hiking near tree line, and annoying his daughter with tales of menacing grizzlies.

o

o

o

e a r l y T R A I N I N G

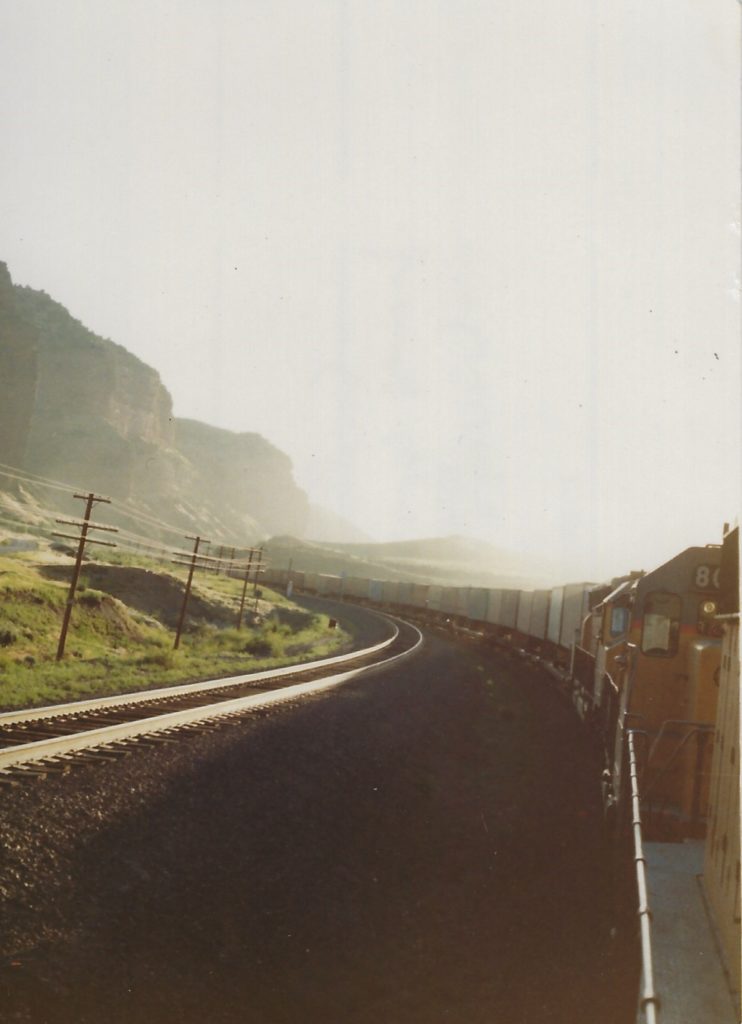

Tom once hopped a freight train from Omaha to Los Angeles with his boss. Close to abandoning their alcohol-nurtured plan in a Union Pacific railyard as midnight approached on a brutally hot summer night, the pair received aid from a sympathetic brakeman. Tom soon had possession of an official forty-page route schedule, along with this piece of invaluable advice: “Ride in one of the extra engines. If anyone asks, you’re with Maintenance Way.” Two mountain ranges, four national parks, and one sprawling desert later, the train slowed for the vast L.A. yards, at which point a voice blared from a speaker built into the control stand: “You have riders in Unit 3. You have riders in Unit 3.” A good minute passed before the engineer replied on that same speaker, “They’re with Maintenance Way.”

Apart from living a number of places – Tom grew up on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River in Dubuque, Iowa, worked in Council Bluffs, Des Moines, Jacksonville, and the District of Columbia – he didn’t make much of his brief internship as a drifter. Witness his final move to Colorado, now more than two decades ago. But he still has his Union Pacific freight schedule, sealed away in a box somewhere, should that lonesome whistle call.

o

o

o

o

o

o

AND AS WITH EVERYTHING ELSE IN LIFE, A SEINFELD CONNECTION

In 2008, October Revolution came to the aid of Jerry Seinfeld. After Dreamworks and Paramount Pictures used the pun, “Give bees a chance,” to promote Seinfeld’s animated Bee Movie, a Florida-based pharmaceuticals firm sued, claiming to have filed for a trademark on the phrase one year earlier. Reading his morning paper, Tom took interest in the story, knowing the pun first appeared in October Revolution‘s Bee-In protest scene. He contacted Dreamworks, suggesting they make the satiric novel, copyrighted in 1998, part of their defense. Dreamworks, arguing the “Plaintiff’s claims are barred because Plaintiff was not the first to use the purported mark in commerce,” prevailed. Interestingly, the Florida firm also claims rights to “Bee In.”

October Revolution, coincidentally, was optioned for movie rights shortly after publication. The project made it to script stage (bad news for one of the main characters, who doesn’t make it to the end of this version), but has yet to see the light of a theater projector.

One more thing…

TOM CAN TELL YOU HOW TO GET, HOW TO GET TO SESAME STREET.

Authors rarely know who is reading their words. Books travel far and not always at great speed. A few years after Geezer Dad was published, it caught the attention of L.A. producers. And if it wasn’t a case of “Hold everything, this needs to be a movie,” the production team was enamored of an anecdote that belonged in a documentary they were making.

The brief account had Tom and his young daughter watching Sesame Street. When Big Bird patiently showed viewers how to properly tie their shoes, the ADHD author realized he had been doing it incorrectly since fourth grade. He vowed to become a better man, choosing to follow a path on which his shoelaces no longer came loose.

The first plan was for Tom to read the excerpt on camera. But after he presented his one condition–the producers would graciously pay for his daughter, now both thespian and teen, to tag along to the New York film site–a new plan emerged. The excerpt was gone, replaced by a one-page script that shared Dad’s life-changing story from his daughter’s point of view. This was the plan for all of a week, after which it evolved into her reading a “Dear Big Bird” letter more in line with what was apparently the overall theme of the series—“Dear [insert name of influential hero/celebrity here]”–in which the documentary would appear.

After arriving at JFK, Dad and kid were chauffeured, dined, and delivered to their hotel. The following morning, in a scene straight out of 100 familiar films, a uniformed security guard opened the gate at Kaufman Studios for the LaMarr entourage. Tours of the Sesame Street sets were provided. Photos, including the one above, were taken. Professional makeup artists attended to the family member with International Thespian Society credentials, while friendly Sesame Street cast members made conversation with Dad.

Hours later, an anxious young woman returned to the famous front stoop where Big Bird and an intimidatingly large film crew had first welcomed her. Dad retreated to the safety of the caterer’s tables, while his daughter hid her nerves like the true professional she was that day. Coached from every direction–the technical crew numbered at least thirty–she read the letter that Big Bird held for her. Better yet, she nailed it on the third take, opening up two days originally scheduled for possible reshoots to see plays, museums, and the magnificent bustle that is New York. (The visit lasted only three full days as it required missing some high school. To this day, one teacher remains skeptical.)

After returning to Colorado, Tom and his daughter wasted no time in violating their non-disclosure agreement by telling friends to watch for the series’ premiere on the soon-to-launch Apple+ streaming service. A retraction soon followed. The producers had been told to reshoot the Big Bird episode from scratch because it didn’t gel with the other episodes honoring human subjects. Receiving dozens of “Well, that’s showbiz” condolences from her friends, Tom’s kid shrugged it off like a true thespian. It had been a great experience, and nothing could erase that. Tom himself could not disagree but regretted that others could not witness the incredible performance that had made him so proud.

Here is the final chapter from Geezer Dad. (Don’t let this stop you from reading the entire book.) It contains the original Big Bird anecdote.

TEN YEARS AFTER

AN EPILOGUE OF SORTS.

I have seen into the future, but only by living it.

Ten years have passed since I first met Evelyn… eight since I visited my hometown and went to an open house at brother Eddie’s to hear someone give me shit, my hometown’s primary source of employment, in the form of “He’s fifty, and he’s got a baby!”

This, if I am to trust a recent refresher in fifth-grade math, makes me fifty-eight, which means that when I stay up to watch the beginning of Saturday Night Live, I say one of two

things upon seeing the host, either “He’s looking old,” or “Who is she?” We have new cats no longer so new, and a dog that chases them. We have one fish. Bubba outlived two others to take control of the tank and food supply. He isn’t much smaller than the cats.

On that long-ago night we borrowed a bassinet from our good friends in Boulder, I was told, “You’re not going to sleep for a while. We haven’t since our first was born. But without

kids, life would get boring.” I have repeated these last words in my head many times, having long come to accept them as truth. Being a parent isn’t all fun, but even with soccer tournaments and the Disney Channel, it rarely gets boring.

I have experienced so many great moments, like watching Evelyn take her first steps. Or making up songs on guitar and violin with an inventive musician who tricked her father, yet again, into giving her a break from her assigned lessons. Or finding myself in total agreement with a seven-year-old’s critique of a novel we were reading together: “She’s not like the Mary Poppins in the movie.”

As it turns out, I was wise to entrust my future to that bib-wearing infant. My daughter has shown herself to be an excellent teacher, which made her the perfect teacher for a student

like me who had so much to learn.

And what exactly was that?

Like parents of all ages, I learned I can take the urgent-care visits, the washable paint spills that turn out to be permanent, and the occasional open rebellion. I learned I can bounce back after getting beat up by ten-year-olds who have too much energy before bedtime and need to release it by physically abusing old people. (She thinks she’s wrestling.) “That’s it, Dad! I’m taking you down!”

Like other adoptive parents, I have talked with my kid about adoption, exploring issues that will give Evelyn’s life its own complexity and depth. From this, I learned that kids come up

with pretty tough questions – most typically when they’re supposed to be closing their eyes for the night. “So what you’re asking, Evelyn, is, did I always know I wanted you specifically, and how could that be possible? Aren’t you tired, sweetie? You’ve got to be tired. I know I’m too tired to consider the possibility that you and I might never have met in a universe

slopped together through a series of random events. What if we talked in the morning?” I do the best I can.

Luckily, as it turns out, my best is pretty damn good. How else to explain my reaction when a baby vomited milk curdled in the oven of a flu-stricken stomach? Holding her out

in front of me, I gently encouraged Evelyn to “Throw up on Daddy. No need to get it on the furniture.” And what of the Christmas morning I waited three hours for antibiotics in the only drug store open that day? Or my devoting four days to hand-painting and assembling a wooden dollhouse before grudgingly giving some mythical clown in a strange red suit all the credit for my labor? I know I get points for that first year of preschool, when every virus with bad intentions followed my daughter home. That’s how I learned that sending a kid out into the world is like having the Europeans “discover” your continent.

There have been bigger surprises, not all clearly marked Good or Bad when they first inserted themselves into our lives. My mother provided the biggest of these when she moved west to make sure Evelyn knew damn well who Grandma was. Seven years later, we’re easily into Mom for thirty grand in unbilled babysitting fees, kid game downloads, and Happy Meals.

Evelyn and Grandma are the closest of friends, as well as colluders and co-stars in Colorado’s longest-running living-room-based improvisational theater. “We’re playing school now, Grandma. You’re the student.” Though well into her eighties, Grandma is every bit the chauffeur, chef, and tutor I am. She forces me to admit I’m not too old to keep plugging away by showing reserves of energy that I hope are embedded somewhere in my genetic code. As for my own relations with Grandma, we’re closer than we’ve been since I was ten. The move has been good for everyone.

The worst two surprises left nothing to ambivalence. Both came this past year, and both had to do with our being older parents. While Evelyn still loves the “strong Daddy” who lifts

her off the ground with one arm, she came close to losing him, along with her mom. Sam took the first blow, when what felt like a pulled muscle turned out to be breast cancer, the very disease that took her mother’s life. She learned this last fall, shortly after we hosted a Halloween party for five of Evelyn’s friends. Upon receiving the diagnosis – Stage 2, detected early – Sam bristled at the thought of being defined as “someone with cancer.” She didn’t want to make pink a big part of her wardrobe.

Evelyn handled the initial news well. Although she turned white when asked, “Do you know what cancer is?” her color came back as she learned more. She seemed to accept we

trusted our doctors and what they were saying. The next five months would be strange, but Mommy would get through this.

The following day, while riding in my car, Evelyn asked questions that were neither too shallow nor deep. “Mom really caught it early?” “The medicine will get rid of all the cancer?”

She would get through this, too.

With Dad and Grandma working double shifts to keep our kid’s life as kid-like as possible, Evelyn continued to have a good year at school. Dad took her shopping for clothes. Aunt

Erin took Mom’s place in a recital audience to hear Evelyn coax sweet, sonorous notes from her instrument of choice.

In grown-up world, our long winter got longer. The doctors’ early optimism – minor surgery, a lumpectomy at most – gave way to the official diagnosis of Triple Negative cancer. “It’s still Stage 2,” the oncologist explained, “but the tumor is larger than we first thought. Triple Negative is a very aggressive cancer.” More surgery was scheduled. This would be followed by sixteen weeks of intensive chemotherapy. Sam’s hair would fall out. Every last strand. She remained tough, making it through surgery and half of her chemo with surprisingly few complaints. Then, with February at its most frigid, the fever hit. One hundred and three… one hundred and four. Knowing that an infection could prove fatal if not treated promptly, we waited impatiently for the oncologist to return our calls. Hours passed. Sam felt queasy, then dizzy. When her fingertips turned purple, we raced to the nearest emergency room, where Sam was placed on oxygen. Technicians administered blood tests to detect infection.

But as we were told, the results wouldn’t be available for days, by which time the antibiotics either would – or wouldn’t – have worked. Late that night, they sent us home to wait and

see. Evelyn stayed with Grandma.

Short of sleep, and shorter still of ideas, I sat at my desk the following morning. Staring at my screen through eyes that had not slept for more than two hours at a time, I wished I could write something to make sense of our tenuous reality, enabling me to reclaim the illusion I had some control over life. But I had gone from being the optimist prone to remarking, “The prognosis could have been much worse,” to being the guy who secretly wondered, “What aren’t they telling us?” Slowly, I typed, Each time we think we’ve finally hit bottom, we learn it’s only another pothole. There is always another, deeper bottom.

I heard Sam in the kitchen, and with some apprehension, went to see what she needed. My wife, by this time, had only two modes: complaining in bed about burning and aching, and

coming downstairs to complain about the dishes in the sink. She couldn’t comprehend that the dishes offered tangible proof that I had been keeping both Evelyn and her, to the extent it was possible, fed. I heated chicken soup. Sam tried to eat some.

Late that evening, after Evelyn had fallen asleep to the sound of Dad’s voice reading Freak the Mighty, Sam’s sister called to ask, “I know you just drove me to the airport a few days ago, but do I need to be there?” I told Erin no, saying there was little anyone could do, apart from washing the dishes I was finally washing.

Watching the water drain out of the sink, leaving a ring of fragile suds, I wondered how Evelyn was processing all that she was seeing. She had to know Mom was sicker than we

had been expecting, but she also knew chemo could beat up its users pretty bad. For what may have been the first time, I pondered life as a widowed older dad. Beyond the shock and

pain, would I be able to pull that off, and what kind of support network would I have? Would Evelyn and I stay in this house? Would we stay in Colorado, or move to the Midwest, taking

Grandma with us, to be closer to Evelyn’s younger cousins, the sons and daughters of my nieces and nephews? These questions brought guilt but didn’t seem out of place.

I heard footsteps behind me, too loud for a cat, too subtle for a dog. “Aren’t you supposed to be asleep, Sweetie?” I asked.

“Is Mommy going to die?”

I knelt down on the kitchen’s hardwood floor, not the best place for ageing knees. “I don’t think so. It just takes her body longer to fight a virus or infection because it’s already busy

fighting the cancer. If you keep painting pictures and giving her hugs… not right now, we’re going back to bed… Mommy should get better.” I could hear the music from Evelyn’s iPod,

still playing upstairs. Grieg. Notturno from Lyric Suite, Opus. It’s in a different playlist from Katie Perry and Taylor Swift, or for that matter, Films about Ghosts and Yellow Submarine

Songtrack, two albums presumably missing from the collections of my daughter’s less fortunate friends.

I offered to sit with her for a while. With little time wasted, she fell back asleep to Pavane for a Dead Princess, adapted for orchestra and played very slowly, which also made for one

sleepy Dad. When I next opened my eyes, her clock read 4:35.

Two days later, the fever broke. The doctors called to say Sam had tested positive for infection, but that it must have been halted, given her recovery, before gaining a solid foothold. The following morning, standing before the toaster, Sam said weakly, “I know you did your best to keep things in order.”

With two weeks lost, we restarted chemo. Friends and relatives lined up once more to display their incredible generosity and concern. Food appeared, already prepared, outside our front door. But this turned out to be problematic, at least for me. I was stressed, and depressed, and surrounded by protein-rich meals meant to keep my wife from losing weight. It wasn’t a good combination.

Sam completed her full recovery in April. All test results read negative – the good negative – and we started planning for a vacation in early June. Together with Erin and other family

members, we would rent a house on North Carolina’s Outer Banks. Once there, Evelyn wouldn’t be able to turn around without finding a cousin to play with. Sam and I would celebrate our renewed optimism by sharing an oceanfront room.

June came, and while preparing to take the dog for his last walk before Pet Camp, I told Sam I needed to call our doctor to review the blood pressure meds I’d been taking for two years. My readings had been slightly elevated, much like my weight. As soon as we returned from North Carolina, I would finally say goodbye to our long winter by addressing both problems.

“You’re not going to call before we leave?” Sam said.

“Too many trip-imposed deadlines. And waiting two weeks isn’t going to kill me.”

Kneeling by our front door, with an easily excited rescue Lab licking my face, I was now tying my shoes. This, I should be too embarrassed to admit, is one more thing I learned as a parent. When Evelyn was four, we caught an episode of Sesame Street in which Big Bird tied one of his freakishly huge shoes. The bird showed great meticulousness, and a series of extreme close-ups made it impossible to miss the slightest detail. I took a personal interest, as this had been my darkest secret since grade school: I did not know how to

properly tie my shoes, having been the kid who daydreamed through countless tutorials, forcing him to later invent his own highly flawed system. There was one little twist I could never figure out, and all through my adult life, my shoes refused to stay tied for more than thirty minutes in one stretch. This slowed me down when racing through airports, hiking with friends, and running from bears encountered while hiking with friends. With my daughter sitting beside me, Big Bird changed all that. Big Bird taught me how to tie shoes, and I was a better man for this. The next bear would have trouble catching me.

Back on my feet, I fastened the dog’s leash to his collar. “I promise to call my doctor as soon as we’re back.”

“I hope that means hours and not weeks,” Sam said, displaying a depth of insight that comes only from decades of marriage. “Otherwise, your doctor won’t be the only one unhappy with you.”

The vacation started with two days to ourselves, during which time we explored the shores north of Cape Hatteras. Driving to our motel on a Thursday afternoon, we stopped to show Evelyn the Wright Brothers monument at Kitty Hawk. After climbing a pissant-by-Colorado-standards hill to reach that monument, an elderly couple took our photo. Then, Sam requested one of me standing alone in front of the word, “genius,” excised from a longer inscription. When I tried telling the strangers, “She intends it to be ironic,” I couldn’t pull up a single word, not even the “to.” In frustration, I stayed silent.

A minute later, I regained the ability to arrange words in sentences. I spoke the six words I had searched for in vain, though my joke had been lost to bad timing. Sam took more photos.

Walking down the hill, I told her what had happened, along with how strange and helpless I had felt. “You’d better drive,” I added. But since she had not witnessed anything unusual, she blamed what I described on heat and exertion. I didn’t point out that our climb had been unimpressive, or that the heat near the beach was hardly oppressive.

Two days later, heading for our final destination, I lost my ability to speak again. While driving across a long, arching bridge, I tried to show Evelyn a raised railroad drawbridge. Words like “rabbit,” “sky,” and “fishing” came out. It was late afternoon, just as it had been when I experienced the TIA.

Turning to face Sam in the front passenger seat, I struggled to let her know some invisible punch had knocked the English major out of me – again – and without using any of the words I was trying to summon, managed to convey the message. “Pull over,” she instructed, and I cut across two lanes of traffic. I got out of the car, and recalling a Red Cross symbol I had seen, attempted to communicate we had passed a clinic or hospital only minutes before. Speaking slowly, and with great effort, I eventually inserted “clinic” between random words like “unless” and “doctor.” I then tried telling Sam I must be having a stroke. I doubt this last word ever made its way out, but she already knew.

Within two minutes, we were facing Carteret Hospital’s Emergency Room entrance. No sooner had Sam found a parking space than I charged out of the car and into the building to

tell nurses I “cow climb tourniquet,” or something that made as much sense.

“Sit down, Tom. Sit down,” I heard my wife say as she took charge.

Then, I was lying in a bed in ICU, while my daughter, looking every bit as concerned as her mom and the nurses, stared at her strange, new dad. Unfamiliar with the workings of a stroke, I assumed it could only get worse. My life would slip slowly away, or worse, my family would fly home with an incoherent invalid for their one pricey souvenir. I would turn my daughter into a caretaker at ten years of age, voiding all my hopes for her future. Smug people would say, “They were too old to have kids.”

When Aunt Erin showed up at the hospital to rescue Evelyn, by taking her to the beach house, one more face stared back with apprehension. I got one last, long hug from my daughter, and watching her walk through the door into the hallway, I realized I might be saying goodbye. For keeps. My heart hurt worse than my head.

Then, to everyone’s surprise, not least of all my own, I began speaking in sentences. And what turned out to be a very localized stroke – three hits to the brain’s left hemisphere where language is formed – showed itself to be in remission. By the time I took my first-ever ambulance ride to a much larger facility in Greenville, I was boring the paramedic with details meant to reassure my brain that it was working properly. My wig-wearing cancer-survivor wife followed in our rental car for all of ninety miles. It was midnight when we reached Pitt County Memorial Hospital.

I spent the next day touching my nose, telling curiously uninformed doctors what year it was, and getting inserted into every large machine the hospital owned. Showing no signs of

physical impairment, I impressed the ICU staff with my resilience. One young guy even called from the hall: “You’re awesome.” I knew I would see my daughter again, and she would see the dad she remembered. The head neurologist promised to get us back to our vacation as early as the following morning, provided my signs stayed good – and I promised to avoid food that relied entirely on salt and fat for its taste, or basically everything served in North Carolina. I would also start taking new blood pressure pills, along with a daily baby aspirin “to keep the platelets slippery.” My brain, he further explained, would construct efficient bypasses around each damaged section of neural highway. It would even recycle the three clots, making use of that material.

Late Monday morning, a nurse delivered my discharge papers. We were on our way to the beach – and Evelyn. When I walked back into the bright, humid air outside, I did so resolving to keep on moving, and for three months now, this is what I’ve been doing. My life continues, albeit with fewer food choices, and I remain more committed than ever before to survive another few decades. I will be there for my daughter.

This is an obligation that can’t be annulled, only modified, even as loving child turns surly teen turns young adult fightingto define herself. Evelyn’s old man will be the real thing then,

no matter how passionately he pleads to be labeled by some other measure. It won’t be enough to just be alive. I’ll have to stay interesting and alert, refusing to prematurely burden

a 25-year-old daughter with tales of hemorrhoids and color-coded pill dispensers. I won’t get to be boring.

These are the choices I made – the choices my child made easier. Ten years into parenthood, I maintain it’s all been worth it, without having to add an asterisk. And if the clock insists on ticking away, then I must keep ticking, too. When my birthday

rolls around this fall, and Sam proudly announces, “I picked up your two favorites, New York Cheese Cake and Boston Cream Cheese Pie,” I will politely decline, saying, “Sorry, but no. I’m saving space for a second helping of broccoli.” And when I buckle seconds later, muttering, “Well… maybe two small pieces won’t do much damage,” I will do so knowing it’s a once-per-year transgression (twice if counting the cherry and pumpkin pie I will eat at Thanksgiving). But for 363 days each year, I’ll be okay with the green stuff. And if I can’t always make the choices I want, at least I’m making choices.

In this scenario, I can still go for walks around Harper Lake, encountering other walkers who look back at a stranger lost in thought, or a neighbor from down the street, or a writer whose second novel is somewhere in their house, or a guy who’s getting a little bit older but doesn’t let it slow him down. And I still get to meet a school bus each weekday at four, to watch Evelyn smile as she bounds off the last step, and looks up to see the part of me that matters most. Dad. Daddy. Old Dad.

I love you, kid. I love you so much I want you to thrive in my absence, to keep treasuring life when I’m no longer part of it. But I also plan to put this off as long as possible, refusing

to write myself out of the story before I have moved furniture into your first apartments, masterminded the mysterious disappearance of an unsuitable boyfriend or two, and sent you countless long-distance emails I know you won’t actually read.

You have already given me more than I ever needed… just this morning, in fact, when you crashed into me with open arms, and loudly declared, “I love my daddy.” And what of that magical, outside-of-time hug you had waiting for me when I returned to our vacation in North Carolina? That had to be the best medical care anyone ever received. For however long it lasted, your dad felt truly awesome.

It’s hard to believe ten years have passed. This, after all, is a lifetime to one of us. As for the old man, I’m a thousand years older than when Mom and I first talked about having a child,

yet younger in so many ways, these lying gray hairs to the contrary. I have never known ten better years, packed as they were with moments I wanted to snatch from time’s grip, refusing to let them pass. On so many occasions, I felt like I was listening to great music, thinking nothing could surpass the melody and richness of texture, only to find the next movement equally satisfying, perhaps even more so because it caught me offguard.

Just as one dad’s epilogue is his daughter’s prologue, life must keep changing, repeatedly, relentlessly. Yet, some of the changes can truly amaze. Having taken the long way to reach

this point, I see no need to rush the last part of my journey, especially if you keep traveling with me. Let’s savor each change, taking our time, however it ends up being measured, in years or in decades. Let’s seize the adventure coming our way.

In the meantime, we’ve got homework to finish and critters to feed. And should we stop to debate how many times one-eighth goes into four, I promise we will sort it out. That’s what

erasers are for – hugs, too. If you learn nothing else from your old dad, apart of course from all this surprisingly advanced math, never forget it’s worth getting things right, no matter

how much patience and persistence are required, whether you’re struggling to master a new piece on violin or trying to reach that place you were always meant to occupy. I know this from experience – you could say, I learned it the long way – and should you need substantiation, then I have a story to tell you someday.

by kind permission of Marcinson Press