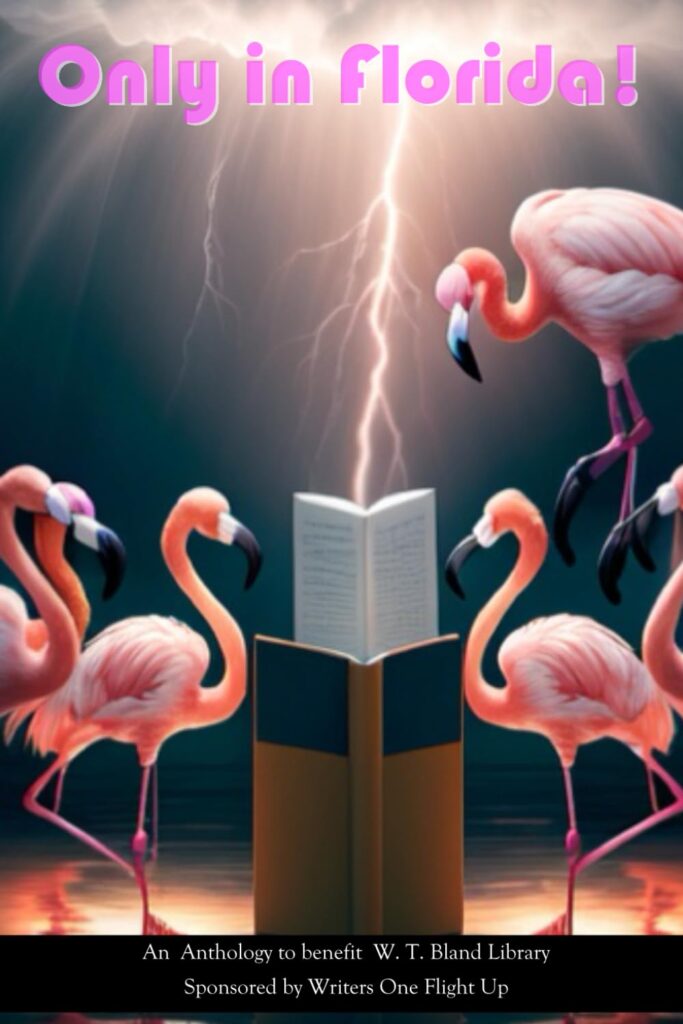

Tom has been busy since completing The Termination Clause. Three summers ago, after his daughter began school in Florida, Tom got a place there, though he draws the line at playing golf and watching Fox News. Instead, he fell back into his decades old writing addiction. In addition to tidying up several novels he had set aside in years past, he earned a reputation as a contest carpetbagger. His short story, “Willie’s Tale,” took First Place in the Only in Florida writers contest and is now featured in an anthology. The book, shown below, can be ordered by clicking these blue words (and the Read Sample button will take you to “Willie’s Tale”).

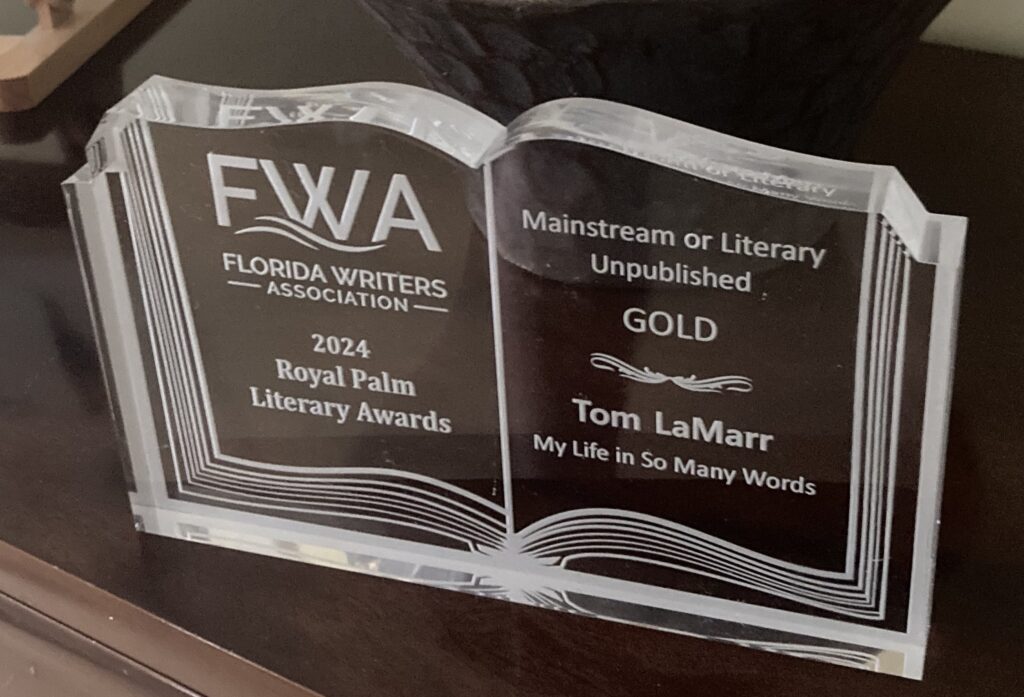

Tom’s novel, My Life in So Many Words, won the Gold Award for Literary/Mainstream Fiction (unpublished) from the Florida Writers Association’s Royal Palm contest. A more polished draft of the novel has been entered in several national and international writing contests.

…

The first of the old novels to get new revisions, Black Ice presents a dark, comedic account of America’s Second Civil War. The first chapter appeared more than a decade ago in Evergreen Review, the legendary literary magazine associated with Jack Kerouac, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Bertolt Brecht, and Edward Albee. Like the rest of the novel, that first chapter has since undergone significant changes. (Excerpt near bottom of page.)

Rath of God, started after Hallelujah City, will one day make a worthy addition to the LaMarr canon, Jah willing of course. When this happens, expect to see the following on the rear dust jacket:

It’s a question theologians and scholars have been asking since the Fifteenth Century, beginning with Pope Pius II. “Why can’t there be a really funny morality tale?”

Tom LaMarr’s Rath of God finally shows how this can be achieved. It is, in the words of one critic, “even funnier than 1425’s classic Castle of Perseverance.”

As for the larger question – does Rath of God answer the fundamental questions of meaning and faith that have perplexed countless generations? – you’ll just have to read it and see for yourself.

Terror on Trail 9 is an old-fashioned middle grade novel that, like The Termination Clause and Rath of God, takes place in Tom’s favorite mythical city, Duchaine, Wisconsin. It’s a Mississippi River town, a few hours north of his less mythical hometown, Dubuque.

Standing Room Only took shape decades ago, before 1999’s October Revolution in fact. Tom had yet to learn the difference between a rough first draft and an actual novel, and as a result, SRO existed for years in a primitive state. But the humor was strong as was its story of an overconfident, young musician traveling from the Midwest to New York to achieve great failure, mostly after forcing a meeting with his own musical hero. (The song lyrics are from original songs, circa 1982, making them old like Tom.)

The Story Tree, as Tom typed on the title page for an early draft, is A novel with everything: sex, drugs, murder, and direct-mail advertising. This was his look at America in the 1980s, a time when a businesswoman walking through a city park while speaking into a clunky, expensive cell phone seemed like an upscale version of the homeless schizophrenic sharing that park. With whom was she speaking? Napoleon? Jesus? Invisible space monsters? Times have changed.

To the perverse amusement of the Midwestern guy writing it, The Story Tree doubled as Tom’s “Southern Novel,” attempting to preserve both the last of the Old South and that brief shining era when writers considered Selectric typewriters to be advanced technology. Tom finished a few drafts before accepting he should have been writing a 240-page comedy to please critics and readers who had noticed October Revolution. (One agent said of The Story Tree, “This would make a great sixth novel. As in, after you’re fully established.”) He abandoned Tree in favor of Hallelujah City. The unpublished novel had its fans, some of whom questioned the decision to set it aside. With the book under reconstruction, perhaps these early readers will live to see justice served.

Some possible future projects:

Memories of Earth, a sequel to Zero Gravity, exists as a third draft, and Tom promises to get back to it soon.

He also occasionally entertains the possibility of writing a sequel to Geezer Dad, having received a number of requests from readers. Now that he is undeniably, certifiably an older dad, he is at least open to the idea, having racked up stories and scars, along with plenty of hard-earned knowledge about the rewards and sacrifices that come with being an older first-time parent. He may even have acquired some wisdom of value to couples considering the same path.

It may not happen, especially if a good idea for another novel comes along. Also, thanks to “Willie’s Tale,” Tom has rediscovered the (comparatively) instant gratification of short fiction. Look for more short stories and essays in the not-too-distant future.

But there could well be an opening chapter in the following piece that appeared in Chicago Now months after Geezer Dad‘s debut in October 2015.

We Got Here Too Late to Leave Early

This is where everything grinds to a halt, where time assumes a physical form, holding me in place, refusing to budge.

Standing outside Gate C-24 at Denver International Airport, I am waiting for Evelyn, my thirteen-year-old daughter, to return from her first-ever plane trip alone. She visited Aunt Mary in Florida. Mary has a swimming pool. Evelyn probably dove in and stayed, refusing to come out for reasons so trivial as food and sleep.

Strangely, or perhaps not, the rest of the world is still moving. Business travelers race past, late for their flights, or simply addicted to hurrying. I stand alone, truly stuck in my own little hell, though this will not last long. Soon, Evelyn will join me here, and I am sincerely wishing I didn’t have to pull her down with me.

After we get her one checked bag, we will stop for lunch in the main terminal. There, I will tell Evelyn about the week she missed in Colorado. Following an emergency room MRI on Monday, doctors confirmed Mom’s cancer is back.

This is why Sam’s arm wasn’t working. A spot on her brain, right on the surface, caused inflammation. She’s in the hospital now, recovering from surgery that, like the ER, had not been on our schedule. (We were planning to shrink our Netflix queue).

I will tell Evelyn that Mom is talking, and that she is very much looking forward to seeing her daughter – the joy of her heart, as Sam described Evelyn to a doctor right before the operation. As for information I will not be sharing, Sam is also facing a whole new world of pain and uncertainty.

The chemo coming her way will be far more intense than when she battled breast cancer some four years before. Worse, it offers no guarantee it will keep her alive. Stage 4 cancer, I now understand, is treatable but not curable. This is more than a subtle difference.

The first passengers disembark, and soon I see Evelyn, the joy of my heart as well. My face feels strange, stretched in directions it hasn’t known these past days. I am smiling. Smiling like a man who just found a way to rejoin the world.

“Daddy!” she squeals the moment she sees me. “Hug!”

A collision ensues, and I deliver the ultimate understatement: “I missed you, kid.”

*

We eat lunch on a balcony overlooking the terminal’s bustling main floor. High above our heads, small birds dart from platform to platform on the columns that support DIA’s signature peaked roof, crafted of canvas and designed, when viewed from outside, to mimic the snowcapped Rocky Mountains.

Evelyn and I share a three-entree Chinese meal from a fast-food restaurant that must be part of a chain found only at airports. Its name wasn’t one I recognized or planned to remember. On the table next to ours, a sparrow pecks at a crispy noodle left behind by other diners.

“On Thursday, when I told you Mom went to the hospital to get her arm fixed, I wasn’t sharing the whole story,” I say as Evelyn smothers a cheese wonton in sweet and sour sauce. “She’s been there since Monday, and on Wednesday, they removed a small lump from the surface of her brain. Her cancer came back, but they seem pretty sure they got it all out. Even so, she’s going to need chemo, and probably radiation this time.”

Again, I see no purpose in telling my daughter everything, like how further scans are needed, or how the doctors are uniform in their lack of optimism, or how Sam looks like crap and feels even worse, having picked up the very strong inference she should start measuring life in months and not years.

“Mom went through this before and came out okay,” Evelyn calmly states while a fluorescent red glob drops to our shared cardboard container. “She’ll probably lose her hair again. She’s not going to like that.”

I take a bite of dried out eggroll and realize I’m through with lunch.

“Look at that bird,” Evelyn says, her head tilted back to do just that.

As I lean back to see, a different bird shoots down toward our table, creating a 3D scene that, in a good Imax movie, would have the entire audience jerking back in their seats. “Woah,” we react in unison, to which I add, “Our food must look better from a distance.” The sparrow lands nearby on the balcony railing, and I can see he really does covet our meal. When Evelyn tells me she’s full, I leave a very small piece of eggroll on the floor between tables. I’m hoping it won’t harm the bird.

“Ready to see Mom?” I ask as she points at the suitcase, letting me know it’s my turn to pull, again.

One hour later, we are walking through an awful place I know too well. Upon reaching the far end of the Neuro Critical Care unit, Evelyn and I enter Sam’s room. My wife, no longer wearing her white turban bandage, smiles for the first time since her operation. “How was Florida?” she asks weakly. “Did you ever come out of the pool?”

*

Look at our birthdays on a calendar, and you will see they’re not far apart. Evelyn’s falls late in her summer vacation. Mine is early September.

Ask about our birth years, and that proximity disappears like matter into a black hole. When Evelyn turns 14 this summer, I’ll hold onto my significant lead at 61.

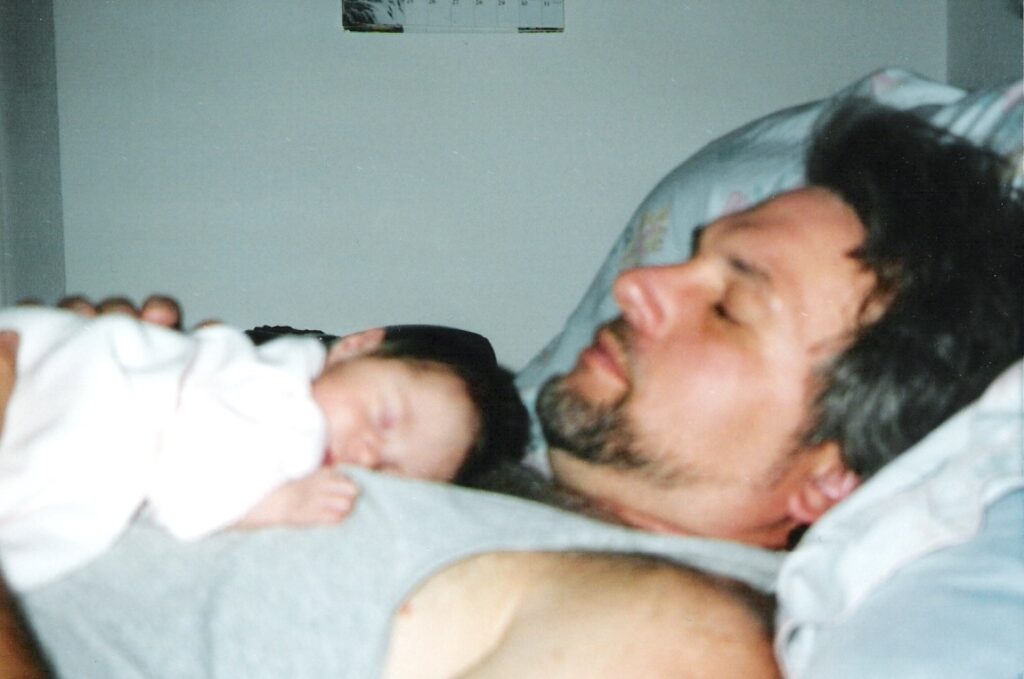

This was not the original plan. True, for our first decade of marriage, Sam and I deliberately held off on starting a family. Like so many others, we believed it couldn’t be that hard to become slightly older parents. A first miscarriage shattered that assumption. Nature and time had teamed up against us, and medical science showed no interest in undoing their malice. Six years passed before we met our daughter.

It was during the adoption process I first had the idea for writing a memoir about getting a late start as a parent. Not only had I noticed I was part of a seismic social trend, which I officially dub the graying of parenthood, but also had been unable to find even one book specifically written to give folks in our situation advice and support. I waited and waited for someone to hand me a copy of this book, but ultimately realized I would have to write it myself.

Soon after I started, an editor who specialized in books about parenting and adoption told me she loved my sample chapters but would never publish Geezer Dad.

“I’m on the other side of the controversy,” she explained over the phone.

“And which controversy is this?” I asked.

“It’s the one dividing the adoption community. Many of us believe that older couples should not adopt. It’s not the first years that pose the problem. It’s the adoptee’s teen years and early adult years. Older parents add the possibility of prematurely turning a child into a caretaker.”

Although I never again heard anyone call this a controversy or saw all that much division in the adoption community, her words stayed with me. I did not want a child turned caretaker, and Sam and I resolved to never let this happen. I addressed these concerns in Geezer Dad.

Years later, as a proud adoptive father, I shared that conversation with our family physician. Dr. Watkins seemed stunned. After telling me that he, too, was an adoptive father, he said, “A child being raised by loving, attentive parents? How could anyone find fault with that?”

“She did have a point.”

“Perhaps,” he said. “But was she right?”

Before this week, I would have said no without hesitation. I would have pointed out that, nearly fourteen years after meeting our child, Sam and I still seemed relatively healthy. We fed, clothed, and bathed ourselves, regularly in fact, and possessed better driving skills than any texting Millennial. With Evelyn only five years shy of graduating high school, we had mastered the art of parenting, going to great lengths to make sure our kid has humor and compassion to balance more perfunctory skills like math and spelling. We were raising an amazing person with a personality that will open many doors for her.

But while that amazing person was shriveling away in her aunt’s Florida swimming pool, a great deal changed. Five years became a very long time. As doctors and nurses seemed all too eager to tell me, only 22% of Stage 4 patients live that long.

Because Sam and I know from firsthand experience how uncooperative nature can be – how it can show an absolute disregard for human matters like plans and love and family – we have long accepted our special responsibilities as older parents. We keep our insurance current; we store medical documents where others can find them. Our wills list nephews and nieces who would do a great job at applying the final brushstrokes to our masterpiece. Not that I’m ready to abdicate that duty. But we believe in being prepared.

We do this because we owe it to Evelyn. We fully understand that our main job in life is to help her become the best adult she can be.

Looking at the short term, we owe her an excellent summer, the one that started with a week in a pool. I will get her to theater camp and hip-hop dance. I will carve time from my Friday afternoons to see and applaud each Final Camp Performance.

Sam, of course, would normally be sitting with me, just as she would be the one reminding us, “We’re going to get through this.” It’s something I happen to believe, as well. We will get through this. But as three? Or two?

That other question haunts me: Were we wrong to become parents at forty-seven and forty-one, respectively? But if I am to be honest with myself, I find this a specious line to follow. The question can’t be answered. All that can really be said with certainty is that we have a funny, resourceful thirteen-year-old daughter to show for our efforts.

As she has from the start, Evelyn brings joy to many lives, not least of all ours. She’s an outstanding citizen of her country and world, and she’s seen more of both than many others four times her age. As you already know, she just made family history by flying to Florida and back all on her own. This marked a big step for her and for us.

For someone in her second year of teenhood, Evelyn is a very caring person. Yet, as promised before, she will not become a caretaker, at least not because of us. She, after all, has people to meet, places to go, and stuff to accomplish. Whether it’s Sam and me, or just me, or just Sam, no older adoptive parent is going to stand in her way. If anything, we’ll stand firmly behind her, for as long as we can, encouraging our daughter to keep moving forward.

Shit happens. We’ve all seen the bumper sticker. And while many bumper stickers lie (you don’t want to vote for angry narcissists), this one does not. The older we get, the more hardship we encounter. All that bad luck we’ve outrun and avoided finally closes in on us. It gets harder to walk down hospital corridors, peek in other rooms, and say, “As tough as this is, it could be worse.”

I remind myself that bad things happen to much younger parents. Many catastrophes don’t discriminate by age. Car crashes, for example, are equal opportunity destroyers and often don’t stop with one parent.

I also know that adversity is part of life, and that a childhood free of it will ultimately produce a helpless adult unable to distinguish small problems from impossible challenges. I keep telling myself that Evelyn could draw strength from this test. But I also keep asking, wouldn’t a scare be sufficient? Do we need a full-blown tragedy? The latter seems cruelly excessive. It isn’t a twist that belongs in our story.

The doctors, so far, have disagreed.

*

Off to the west, crowning the mountains outside my window, dark clouds are churning, a storm in the making, early for a summer day in Colorado. Five weeks have passed since Evelyn returned from Florida, and she’s out for the day, enjoying her Jewelry and Metalworking Camp at our town’s cultural center.

I hear Sam in the next room. Not only is she home, but she’s also moving around on her own, if aided by a walker. She complains more than usual but is every bit as intelligent as she ever was and almost as mobile as she was right before the surgery.

Impressively, when Evelyn said her mom would survive this, she got it right, unlike our oncologist, surgeon, and two other physicians. A CAT scan and bone scan showed nothing more in the way of cancer, and the world’s most negative medical professionals turned surprisingly optimistic.

“Sam’s first cancer was Triple Negative,” the oncologist told us. “That is very bad. This is HER2 positive. We have a much better target. This is still considered breast cancer metastasis, making it Stage 4, but I believe it is potentially curable.”

Pretending to be the forgiving sort of person I have always aspired to become, I did not ask, “So why did I hear the ‘treatable not curable’ mantra at least twelve times during Sam’s hospital stay and onsite physical therapy?” I simply said, “That’s great news.” Because it was.

Ready to start chemo in three weeks’ time, Sam’s proving herself the fighter she was in Round One. In the meantime, I’m taking sides in a fresh controversy: the one about the impact of positive thinking on cancer. I believe it’s a factor and that Sam is the proof. She wants to watch her daughter grow up, and she’s going to do it.

As for me, if there is any justice in this world, the broccoli and spinach I’ve been eating will keep me alive. I’ll watch my kid graduate from whatever she needs to graduate from. I will be there, honoring the promise made in Geezer Dad to stick around until I have moved furniture into her first apartments and masterminded the disappearance of an unsuitable boyfriend or two.

Furthermore, I will continue to enjoy life’s little moments, many of which are certain to have Evelyn at their center. I will get up every morning and do the best I can, and yes, I will remain an advocate for adoption, even for folks who are, right now, wondering if they waited too long to start families.

Leaving you with a much better ending than I originally thought we were headed for, this Geezer Chauffeur must now excuse himself. Summer camp concludes at three, and someone there will be looking for Dad. Evelyn will want to see Mom, as well, and I’m happy to say I can arrange this once we are home.

I might even bring Sam along to the Final Jewelry Making Demonstration on Friday. I’ve heard rumors she could be getting a custom-made steel necklace complete with copper heart pendant. After some of the surprises that have come her way lately, I have a strong hunch she’ll enjoy this one.

Finally, as promised, here is the excerpt from

BLACK ICE

“We are Americans. God’s people. We don’t learn from mistakes. We teach from mistakes.”

—Reb Post, 49th President of the United States

Slick now understood why he heard artillery fire during the night. It had been aimed at the plane that dropped the leaflet he held in his thick, gray glove, the leaflet urging citizens of Alaska still loyal to the American government to find safe ground, further defined as “at least fifty miles from the nearest Black Ice enclave.”

“They’re wrong to call this the Second American Civil War,” Lieutenant Toole addressed the troops standing in formation in Wasilla’s town square. “This is the new Crusades.”

Whether or not it was merely for show, Toole projected the confidence of a leader who didn’t know he and his men would soon be firebombed or gassed. He was a man who, in appearance at least, had not properly interpreted the messages delivered without leaflets: two southeastern Alaska towns obliterated by an American President, and Russia advancing across the Aleutians, effectively declaring that, in severing ties to the United States, Alaska had reverted to previous ownership.

“America is the Holy Land,” Toole continued, his words turning to steam the instant they left his mouth to hang briefly in the frigid air like silky, tattered flags, “and we are taking it back for Christ.”

Even had Slick believed Black Ice held the slightest chance of succeeding, he had no desire to take anything back for Christ. All he wanted was to be warm again, a simple ex-contractor back with the ex-wife who had grown to love him in absentia. He wanted to be far from this stupid, simmering war, a good thousand miles behind what the idiots gathered with him in the square believed to be enemy lines.

The rims of their fur-lined arctic hats pointed skyward as a black speck passed slowly overhead, high in the silver-blue sky, another CIA drone. Piloted by computer warriors in the spook-world equivalent of a mall arcade some 4500 miles away, the plane was capable of raining down death or—Slick’s stated preference—spying on troop locations. The speck moved on; he resumed breathing. At least it was warmer this morning in April of 2037, though Slick suspected that his own standards for comfort were simply dropping to conform to their surroundings. Crumpling the leaflet and letting it fall to the still-hard ground, he smiled, imagining how tropical suburban Denver would feel to him now.

.

.

Title page from Evergreen magazine 2010